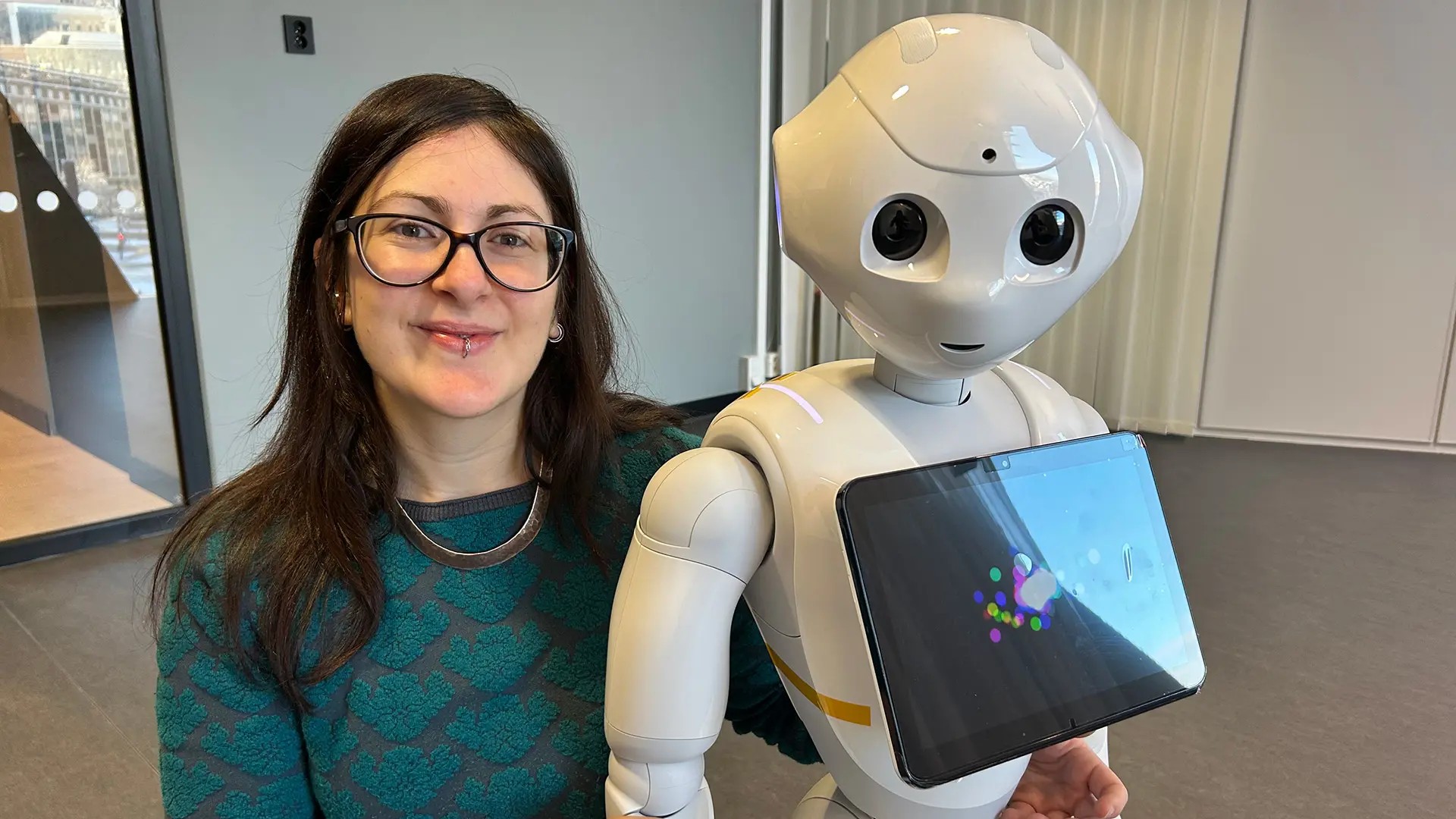

Imagine robots helping out in schools, at the doctors’ office or in a retirement home. To make this a reality we first need to understand, and improve, the social interaction between humans and robots. Assistant professor Ilaria Torre at the department of Computer Science and Engineering (CSE) aims to do just this, with a little help from robots like Pepper.

Pepper, the social robot with big eyes and a smiling face, arrived at Chalmers not long after Ilaria Torre herself last year. It has just participated in an experiment investigating how humans and robots navigate a crowded space, Ilaria Torre’s latest research-projects on human-robot interaction. Ilaria Torre studies the social ways in which humans interact with robots or vice versa, and a crowded common space creates such a situation dictated by social norms. People keep a certain distance, don’t walk into each other, and move faster with a stressed facial expression when in a rush, and robots need to follow the same social rules to be able to coexist with humans in society, Ilaria Torre explains.

“A robot could need to be in this space to for example make a delivery or clean the floor, but robots don’t have access to facial expressions, body language, or changing speed in the same way as humans. In this environment we need to find an intuitive signal from the robot that makes people understand that the robot is in a hurry for example”.

How gendered voices risk strengthening stereotypes

With a background in linguistics and phonetics, Ilaria Torre’s main interest is communication, language, and speech. That involves both non-verbal communication such as the crowded space-experiment, and verbal communication, how the robot speaks.

“We derive a lot of information from hearing someone’s voice for the first time. Since robots are not restricted by biology like people, and since technology has drastically improved the quality of the voices we can make, we have a unique opportunity to design appropriate voices for robots”, Ilaria Torre says. But, she continues, with this opportunity also comes a lot of responsibility to not reproduce stereotypes.

“A few years ago, there was a discussion about how Siri and Alexa’s default female voices risked associating servitude with femaleness, especially among kids growing up with these tools. Most robots will have a servitude task and we want to be careful not strengthen those stereotypes”.

Through one of her experiments, Ilaria Torre found that when people where shown a robot with a masculine or feminine shape, and asked which gender it was, they were more likely to gender the robot if it also had a male or female voice. When that same robot was given an ambiguous voice, the gendering decreased. Part of Ilaria Torre’s research now is about generating new voices that are disruptive in this sense, making gender ambiguous synthetic voices. The next step in her research is to see how these voices affect stereotypes.

“The problem is not giving the robot a gender; the problem is stereotyping. Less association to gender could hopefully reduce stereotyping in the future”, she says.

The dilemma of the human-like robot

According to Ilaria Torre the historical reason that robots have been created human-like in the first place is so that people will know how to interact with them. But this comes with some pitfalls, such as the “too” human-like robots.

“This is where the term uncanny valley comes from. When you encounter something very human-like that does not have all the human features it becomes uncomfortable and creepy”.

Another problem with too human-like robots, she continues, is that it gives you very high expectations on the robots. The robot Pepper for example has eyes and therefor you assume it can see, it has a mouth so you assume it can speak. But it also has fingers so you assume it can grasp, which it cannot.

“When a robot cannot deliver on your expectations trust and willingness to interact decreases.”

For Ilaria Torre it is important to create robots that can be trusted and deliver on what they promise. She believes that social robots can really help people on a community level and for that reason she wants to bring them into parts of society where they are not yet used.

“Most people can probably see the advantages of using robots for tasks humans cannot do, such as precise repetitions, heavy lifting, or dangerous situations. But there are many benefits of using robots in social situations. Studies have for example shown that people with conditions or illnesses that carry a stigma are less hesitant of describing their symptoms to a robot than a human doctor. Another example is robots in school. A good way for kids to learn is by teaching someone else, which they can do with a robot.”

Creating trust in robots

The robot Pepper resides in Kuggen at campus Lindholmen and most people that pass it comment on its cuteness. This is not accidental, a robot’s appearance is one of the factors that influence people’s trust, explains Ilaria. Design, voice or behavior are robot related factors which researchers can affect. Human related factors, such attitudes towards robots are harder to change.

“There is an age difference where older people tend to be more reluctant towards robots. There are also cultural differences, in Japan robots are much more accepted which might partly be because of how robots are portrayed in their popular culture. Robots in western popular culture are usually framed as villains”, says Ilaria Torre.

It is important to remember that robots are just tools, Ilaria Torre continues, and the risks they pose depend on who is behind them. Researchers can minimize that risk through transparency and accountability.

“Most robots are going to be powered by AI soon. This is where proper design comes in, we need to be transparent with what the robot can and cannot do. We also need to involve people in the design in order to learn about the robots and hopefully understand their limitations. Finally, for us to be able to trust a robot, we need to make sure that if a robot makes a mistake, it acknowledges it and apologizes”, says Ilaria Torre.